I found a few of these in a strange little box of visual puzzles and optical illusions that I've had for years, and thought they'd be an interesting thing to try for today's elephant. And yep, "hold-to-light" is their technical name.

The concept is simple. On the front, there is a conventional image of some sort. When it is held up to the light, however, it changes in some way. This is because the reverse side features elements such as an altered background, additional figures, black to block out the light, and so forth. In more elaborate versions, there are either holes in the card, or a translucent or transparent film through which the light shines through, evoking the moon or stars, for example.

Most hold-to-light images were sold as postcards or advertising cards. Today, there are many aficionados and collectors of hold-to-light cards, and various opinions on what constitutes a "real" hold-to-light image.

To give you an idea of how this works, I've shown three of the ones I have, from the front, from the back, and with light shining through from behind.

|

| Universal Clothes Wringer advertising card, 1880. Source: Julian Rothenstein, The Paradox Box: Optical Illusions, Puzzling Pictures, Verbal Diversions, London: Shambala Redstone Editions, 1999. |

|

| The Destruction of Pompeii, 19th century. Source: Julian Rothenstein, The Paradox Box: Optical Illusions, Puzzling Pictures, Verbal Diversions, London: Shambala Redstone Editions, 1999. |

For today's elephant, I thought I'd try to make a couple of these. Nothing quite so spectacular or detailed as the example above, I'm afraid, but you'll get the idea if you want to try this on your own.

I couldn't find any instructions online on how to create these, so you'll only have my made-up technique to go by for now. But I think it's probably no more involved than what I've described below.

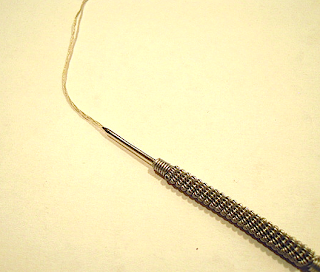

I figured that the most important thing here was paper choice. It needed to be thin enough to let light through, but heavy enough to take drawing and/or ink on both sides of the paper, without anything bleeding through. I used an inexpensive sketchpad paper, cut into relatively small 11.4 x 14.6 cm (4.5 x 5.75-inch) sheets, and decided to use a fine-point artist's pen and coloured pencils. I decided against paint, because I didn't want the paper to get too wibbly.

To start, I lightly sketched an elephant on the front. When I was happy with it, I darkened the lines with ink. I decided to save the colouring for later, just in case I ran out of time.

Once the front was dark enough to see when held up to the light and viewed from the other side, I flipped it over and added whatever extra details I liked. As with the thaumatrope, you can use a lightbox, a window with light shining through, or a piece of glass over a lamp to help you draw the reverse image.

I then coloured both front and back. Colouring isn't really necessary; it just made it look more finished to me. Besides, I like colour.

Here is what each looks like from the front, then from the back, followed by what it looks like with light shining through. Normally the back would feature a full scene that holds together visually on its own when flipped over—although this is not always the case, even in traditional hold-to-light images. It's been a long day for me, so I wasn't quite creative enough to think of an entire scene, although I tried to go in that direction in the second one I made.

I liked this activity. It would be a fun thing to do for kids, and would probably make cool greeting cards. It's certainly not difficult, and each drawing took me only about half an hour, including colouring time.

Next time I do this, however, I think I'd try to make full scenes on both sides. But for now, I really like the way these look when held up to the light, and the colour comes through quite nicely. Despite my rather childish scrawls, they even look vaguely vintage in the right light.

Elephant Lore of the Day

Despite their size, adult elephants have been known to hide from humans. Some of them are even quite good at it.

Elephants generally choose brush and jungle as their hiding places, and seem to have developed an uncanny instinct for the types of patterns that best conceal them. The two photographs below show elephants hiding in plain sight. For an elephant caught in the act of disappearing, check out this video.

To Support Elephant Welfare

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation