Today I thought I'd try a sizeable watercolour painting, which is something I've never attempted before.

Painting with water-based pigments likely dates as far back as palaeolithic cave painting. In Ancient Egypt, water-based paints were used in manuscript illumination—a purpose they served until well into the Middle Ages in Europe. Watercolours also have a long tradition in Chinese, Korean and Japanese painting, where they are used primarily for monochromatic works in black and brown. Countries across the Middle East, as well as African nations such as Ethiopia, and South Asian countries such as India and Sri Lanka, also have significant watercolour traditions.

Watercolour's modern history in Europe starts during the Renaissance. German artist Albrecht Dürer is considered one of the earliest artists to adopt and master the medium, and is renowned for his detailed nature-based watercolours.

During the Baroque period, painters generally used watercolour paint only for sketches. A few artists used watercolour for small-scale works during this time, with subject matter that was generally botanical or otherwise nature-based. Today, watercolours remain the medium of choice for wildlife and botanical illustrators—as the Wikipedia page on watercolours puts it, because of "their unique ability to summarize, clarify and idealize in full colour." One of the foremost proponents of this type of work was nineteenth-century naturalist and artist John James Audubon, whose original wildlife watercolours are considered latter-day masterpieces.

In England during the eighteenth century, watercolours became a popular painting medium. This was largely because watercolour painting was considered an important accomplishment, particularly for well-bred young women. The medium was also valued among mapmakers, military officers, engineers, and surveyors, for its ease of use in the field to depict buildings, terrain and geology. Watercolour artists were also frequently brought along on archaeological expeditions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and no young man's Grand Tour was complete without a collection of painted watercolours he had either produced or purchased on his travels. Important watercolour artists of the time included Thomas Gainsborough, John Robert Cozens, Thomas Hearne, William Blake, and Joseph Mallord William Turner.

During this time, watercolours began to truly come into their own. They were now being used to produce large works far removed from their original nature-based subject matter, with content ranging from historical and mythological scenes to architecture and romantic landscapes. Watercolour societies were formed, and soon there were galleries featuring exhibitions of watercolour works. The medium even generated its own controversies, as artists developed rivalries and debates regarding the relative merits of densely pigmented watercolour, versus more delicate and transparent hues.

The popularity of the medium would also lead to many innovations, including heavier papers and special brushes. Books and courses were developed, as were new types of paint and accessories. New discoveries in chemistry also played a part—quickly adapted to the production of new pigments, including prussian blue, ultramarine blue, cobalt blue, viridian, cobalt violet, cadmium yellow, aureolin (potassium cobaltinitrite), zinc white and various new reds. Although often developed first for watercolours, these bright new pigments soon found their way into all painting media, in turn stimulating the general use of stronger colours. In many ways, the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries might be said to have been the golden age of watercolours.

Although watercolour painting was as popular in the United States as it was in Britain during the nineteenth century, it was less popular in Europe. Some artists, such as Honoré Daumier, Eugène Delacroix and Paul Cézanne produced fine watercolours; as a medium, however, it remained less popular than oil painting.

One of the greatest drawbacks of early watercolours is their instability when exposed to light. When the British Museum inherited some 20,000 paintings by J.M.W. Turner in 1857, it was quickly discovered that the aniline dyes and pigments in his paints faded rapidly in sunlight. This led to a re-evaluation of the permanence of watercolour pigments, which led in turn to a sharp decrease in their popularity.

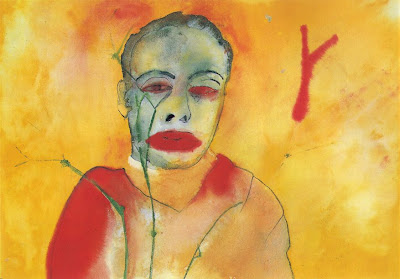

In the twentieth century, many European artists continued to produce important works in watercolour, including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Raoul Dufy and Egon Schiele. Americans such as Edward Hopper, Georgia O'Keeffe, Andrew Wyeth, Eric Fischl and Francesco Clemente have also produced stunning paintings using watercolours.

|

| Fire, 1982 Francesco Clemente (1952– ) Source: http://www.blogger-index.com/1791248-drawing-3 |

Modern watercolours are far more stable than the paints used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Today's watercolour paints contain four primary ingredients: pigments (natural, synthetic,

mineral and organic); gum arabic as a binder and fixative; additives

such as glycerin, honey and preservatives to alter various properties

such as viscosity and durability; and a solvent (usually water, although other watercolour solvents exist), which is essentially

what is used to thin or dilute the paint, evaporating when the paint

dries.

Although "watermedia" means any painting medium that uses water as a solvent—including ink, tempera, gouache, acrylic paint

and watercolours—the term "watercolour" specifically refers to paint

that includes water-soluble complex carbohydrates as a binder. In the

sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, these binders included sugars and

hide glue. Since the nineteenth century, gum arabic has been the preferred

binder, with glycerin and/or honey added to improve the spreadability

and solubility of the gum arabic.

Watercolour painting is currently enjoying something of a resurgence among artists. Its portability,

delicacy and ease of use often make it one of the first forms of painting media

to be adopted by artists, and virtually every child has had some

exposure to water-based paints from an early age.

For today's elephant, I decided to work on a piece of ridiculously expensive Whatman watercolour paper (a generous gift from my husband), measuring 22 x 30.5 cm (9 x 12 inches). For paints, I chose a mid-range paintbox that's been around the world with me—in fact, the only set that's actually been to India, so it seemed appropriate to paint this particular elephant. As long as I have reasonably pure pigments to work with, it's easy enough to mix virtually any colour, so I didn't need a lot of paint choices—just good ones.

Because I wanted this to be fairly realistic, I chose to work from the following photograph:

I have to admit that I wasn't very confident starting out. I'm no expert when it comes to watercolours, being completely self-taught, so painting something with subtle shading without turning it into a murky mess was a bit daunting. Because of my lack of confidence, I started by drawing the major contours with the faintest of pencil lines. So faint that I didn't bother photographing them.

Next, I went over the major lines with a very thin line of dark black-brown.

Still lacking confidence, I looked for the very darkest shadows and put those in.

Since disaster hadn't struck yet, I started looking for other shades of brown and black, adding in each new shade wherever I saw it in the drawing. I guess it's a bit like a paint-by-number approach to watercolour, in that I did one colour at a time across the whole drawing, but I didn't think I would be able to manage more than one colour at once. I'm not sure if this is the right way to produce a watercolour or not, but it worked for me. This time, anyway.

When I felt that this was almost finished, I went back into various areas and shaded them some more. The final touch was adding very fine almost-black lines to give a little more dimension to certain areas, and to add some wrinkles. I didn't want to go overboard with the wrinkles, so I only added a few in each area to give the feeling of wrinkles without going crazy. The kind of lines I'm talking about are most visible around the eye.

I'm pleased with the way this turned out, given my rudimentary skills. If I were truly trying to reproduce the photograph, I should probably have used a much more opaque painting technique, but I'm happy enough with this as it is.

It was an interesting learning experience, and took a little under two hours from sketch to final, so it wasn't a huge investment of time. But next time I think I'll work smaller, and probably on something more colourful.

Elephant Lore of the Day

The photograph that inspired this watercolour sketch mentions the "Lord Ganesh festival", which is celebrated in India between mid-August and mid-September each year. This ten-day festival honours Ganesha, the elephant-headed god of the Hindu pantheon.

Ganesha is described in Hindu mythology as the child of the god Shiva and the goddess Parvati. The most common origin story for Ganesha is that, one day when Shiva was away, Parvati created Ganesha out of the sandalwood paste that she used for her bath, then had him stand guard at her door while she bathed. When Shiva returned, Ganesha didn't know who he was, and refused him entry. Enraged, Shiva cut off the child's head, then stormed inside the house. Realizing too late that he had beheaded his son, Shiva placed an elephant head on the child's body, and Ganesha has been an elephant-headed god ever since.

Ganesha is the Lord of Obstacles, responsible for both placing and removing obstacles. He is also the god of letters, learning and wisdom. In some traditions, he is the god of new beginnings as well, and is invoked at the beginning of any new venture or journey.

|

| Figures created for the Ganesh Festival in India. Photo: Vijay Bandari Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ganesh_mimarjanam_EDITED.jpg |

To Support Elephant Welfare

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

No comments:

Post a Comment