I've made cinderella stamps for this blog, so today I thought I'd make a couple of postmark-cancellation mark combinations to go with them.

Postmarks are official markings on letters, packages, postcards and other mailed material, bearing the date—and often the time—that the item was received by a postal service. Today, postmarks are often applied at the same time as the cancellation or "killer" mark, which indicates that the postage has been used. Sometimes the postmark and cancellation mark are separate, and sometimes they form a continuous design. Occasionally postmarks appear without a cancellation mark.

|

| Cover with postmark, cancellation bars, and railway stamp (upside-down in blue), 1913. Photo: Bill Coates Source: http://www.judnick.com/judnick/maritimepostmarksociety.htm |

There is a certain degree of confusion about what constitutes the postmark. The postmark is specifically the mark indicating date, time and place. The cancellation mark, or killer, consists of the lines or bars used to cancel a postage stamp. The "pre-cancel"—as, for example, when postage is rubber-stamped at a postal counter—is also not a postmark. The rubber stamps known as "flight cachets", indicating the flight on which a cover has travelled, are applied in addition to a postmark, and are not considered postmarks, either.

Postmarks are either applied by hand or by machine, although there are a few unusual variations. These include the embossed postmark of the Underwater Post Office at Hideaway Island in Vanuatu, a rubber-stamp postmark in Hawai'i which included hand-painting, and a stereoscopic postmark which offered a three-dimensional effect when a special viewer was used.

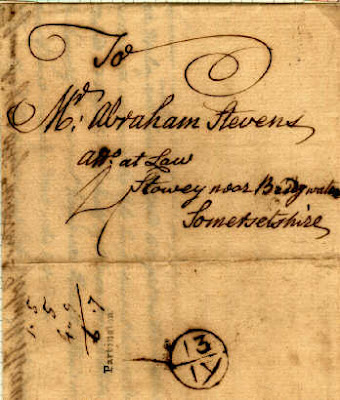

The first known postmark was introduced in England in 1661 by Postmaster General Henry Bishop. Known colloquially as a "Bishop Mark", it showed the day and month of mailing, as a way of preventing the delay of mail by postal carriers. Bishop Marks lasted until 1787–1788.

During the later seventeenth century, a number of postmarks were produced for the London Penny Post, which involved delivery of mail within the city of London. The postmark itself bore the initial of the post office it was sent from, along with a separate time stamp. The postmark indicated that postage had been paid, essentially functioning as postage stamps do today.

When the world's first postage stamp—the Penny Black—was issued in Britain, the ink was red to show up against the black of the stamp. This was considered impractical, and stamps were given colour instead so that black ink could be used for the postmarks. This first postmark was nicknamed the "Maltese Cross" because of its shape and appearance, and was used in conjunction with a date stamp. Today, most postmarks are still black, with red as a second choice.

|

| Penny black with red postmark, 1840. Source: http://stampauctionnetwork.com/f/f12163.cfm |

By the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, letters often ended up with multiple postmarks, indicating the time, date and location of each post office handling the letter. This is still occasionally the case, although most mail features only the postmark of the originating country.

There have been many types of postmarks over the centuries. The Pony Express had a variety of postmarks for the mail it carried across the United States, only 250 examples of which are known to exist today. There have been postmarks for raillway post offices (RPOs) and postmarks for ships—and even a surfboard postmark in Hawai'i for mail that travelled by surfboard. There are "censored" postmarks with the time and place of mailing obliterated. In a similar vein, "clean" postmarks bearing minimal information were used on naval vessels during wartime, in order to keep route details from falling into enemy hands.

|

| Pony Express

postmark, 1860. Photo: Richard Frajola Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pony_Express%2760_ West_bound_1860.jpg |

In the period before 1900, postmarks nicknamed "fancy cancels" were prevalent in the United States. These were often hand-cut from cork by the postmaster himself, in elaborate shapes including seasonal shapes, stars and flags. Surprisingly, you can sometimes apply for a permit to use your own postmark, called a "mailer's permit postmark" in the United States.

Although elaborate postmarks are less and less common, almost all of today's postmarks still indicate both a location and date. A notable exception is New Zealand, which in 2004 decided to eliminate the location on their postmarks, keeping only the date. Another exception is the postage printed via computer, which already comes with a built-in cancellation barcode. Some countries also offer "postmark advertising", allowing people to advertise on the cancellation mark.

Postmarks are used to confirm mailing date, and can be important under certain circumstances. In some countries, for example, a postmark can serve as proof that income tax returns were filed on time. Postmarks are also frequently used to determine contest eligibility.

Today, there are a number of postmark-collecting clubs. Special or rare postmarks can also add significantly to the value of postage stamps, as can cancellation marks that include advertising, or other interesting images. So valuable have postmarks and cancellation marks become that there is an underground market in philatelic forgery, often involving changing the date of a postmark or cancellation mark, or otherwise altering it in some way.

For today's elephant, I decided to use a black pigment liner, and cold-pressed watercolour paper. I also pulled out a bunch of drawing templates I had from various courses I've taken over the years.

It was a pretty straightforward process: sketch the postmark, then ink it in. The main issues for me involved lettering, which is more or less my nemesis when it comes to work like this.

I sketched three different designs for an Elephant and Castle postal station. I don't know if there ever was a specific Elephant and Castle postal station in London, but it didn't really matter for something like this.

Some of the things I took into consideration when making these:

1. I wanted them to be about the size of actual postmarks, so I chose a 1-1/4 inch (3.17-cm) circle for the two with circle outlines.

2. I needed to include both the name of the place and the date, so I had to think about where to leave space when drafting the designs.

3. The designs had to be graphic and not too fussy, while still including elephants.

4. While circles are traditional, I also wanted something less conventional, so I decided to make an elephant-shaped space as well. Other shapes I thought about trying included triangles and squares, but I didn't think I should spend all day on this activity.

Once I had my three sketches, I inked in the elephants and the circles.

Then I tackled the lettering. I hate lettering by hand. It never looks as even as I hope it will, and I can never get the spacing right. So, while it took me about half an hour to conceive, sketch and ink all three designs, it took me about an hour to space and pencil in the lettering, respace and resketch it, and so on. And then ink it, which resulted in less stellar results than I had anticipated. Oh well.

Aside from the lettering, this was rather fun. Making a custom postmark for an art project is easier than you'd think, particularly if you have templates you can use, and are good at lettering. I'd designed postmarks for a series of world music posters years ago—albeit on a computer—and had forgotten how interesting an activity it can be.

Although I wouldn't do this every day, once in a while it's worth the trouble.

Elephant Lore of the Day

My friend Peter mentioned ballet and elephants this morning, which reminded me of the story of Igor Stravinsky's Circus Polka.

Circus Polka: For a Young Elephant was written in 1942 for George Balanchine, who had been hired in 1941 by the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus to choreograph a number involving ballerinas and elephants.

George Balanchine had known Stravinsky since 1925, and suggested to the circus that Stravinsky be hired to write appropriate music. When the circus agreed, Balanchine called the composer. Balanchine remembered the initial conversation as follows:

Balanchine: "I wonder if you'd like to do a little ballet with me."Although Stravinsky was busy at the time, he negotiated a high fee with the circus for a short piece, which he composed for piano in a matter of days. The subtitle "For a Young Elephant" alludes to the phone conversation with Balanchine.

Stravinsky: "For whom?"

Balanchine: "For some elephants."

Stravinsky: "How old?"

Balanchine: "Very young."

Stravinsky: "All right. If they are very young elephants, I will do it."

Stravinsky was no longer involved by the time the ballet was performed by the circus, and the music was arranged for organ and a concert band by David Raskin. Balanchine's final choreography included fifty elephants and fifty dancers, led by the Asian female elephant Modoc, and by Balanchine's wife, principal ballerina Vera Zorina. All of the elephants, including the males, wore pink tutus.

The video below—narrated in Russian, but with the only archival material I could find—features stills from the ballet at about the 4:25 mark.

There was some initial concern that Stravinsky's music might cause the elephants to panic and run wild. (Remarkably, Stravinsky's music often does similar things to me.) The elephants were remarkably calm, however, and Balanchine was actually able to teach Modoc the choreography himself.

When the ballet debuted at Madison Square Garden in April 1942, it was an immediate hit. It was performed another forty-two times, although Stravinsky never attended. Despite his disinterest in the circus version of his Circus Polka, however, Stravinsky did rearrange his original piano piece for full orchestra a couple of years later. The video below features the orchestral version.

Following the first performance of the orchestral version, it was performed a number of times on radio to support the U.S. Army, then fighting overseas. Stravinsky reported that, after one such broadcast, he received a telegram from an elephant named Bessie, who had performed in the original ballet. Stravinsky later met Bessie in Los Angeles.

The Circus Polka has long been in the repertoire of many orchestras, and remains popular today, particularly for children's concerts. It still lives on as a ballet, as well. Balanchine re-choreographed the ballet in 1945 for a one-time performance by students of the school of the American Ballet Company. In 1972, choreographer Jerome Robbins, then ballet master with the New York City Ballet—founded, incidentally, by Balanchine—created a new ballet to Stravinsky's music, featuring young dance students and an adult ringmaster. It has since become a regular piece, often featuring guest ringmasters such as Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Nor does the story end there. In 2006, Leda Schubert wrote a children's book with illustrations by Robert Andrew Parker called Ballet of the Elephants, telling the true story of the original Circus Polka.

|

| Poster for the Circus Polka, 1942. Source: http://yesterdaystowns.blogspot.ca/2008_11_01_archive.html |

To Support Elephant Welfare

Elephant

sanctuaries

(this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information

on a number of

sanctuaries

around

the

world)

No comments:

Post a Comment