I wanted to call today's activity sumi-e, but I discovered that this particular technique doesn't actually originate in Japan, but in China.

Ink-wash painting developed in China during the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–907), later spreading to Korea and Japan. The goal of this type of painting is apparently not to reproduce the exact appearance of the subject, but to capture its soul. According to the Wikpedia page on ink-wash painting:

To paint a horse, the ink wash painting artist must understand its temperament better than its muscles and bones. To paint a flower, there is no need to perfectly match its petals and colors, but it is essential to convey its liveliness and fragrance. East Asian ink wash painting may be regarded as an earliest form of expressionistic art that captures the unseen.I'm doomed.

|

| Beauty and Elegance Spreading 10,000 Miles by Chen Zheng-Long, 2008. Source: http://www.orientaloutpost.com/proddetail.php?prod=1h-czl1 |

Asian ink-wash painting has also had a significant impact on Western art, particularly in modern times. American artist and educator Arthur Dow, for example, advocated using the ink-wash technique to make a visual impact using the fewest possible lines and shades. Dow is in fact credited with encouraging a more free-form approach in modern American painting, by suggesting that his students—one of whom was Georgia O'Keeffe—practice with East Asian brushes and painting techniques.

Apparently it takes years to develop a facility with Asian brushes, let alone an ability to produce the requisite range of colour and line. In the hands of a master, a single brushstroke can have a tonal range from deepest black to silvery grey. I've never been very adept with the one Asian brush I own—which is probably why I've never bought more to add to my extensive collection of brushes—so this could be interesting.

|

| Crow Series IV by Jean Kigel. Source: http://thelittlelies.tumblr.com/post/224065234 |

To produce the right kind of ink, artists usually grind an inkstick over an inkstone. Traditional inksticks are made of soot combined with animal glue, and the inkstone is a sort of rough slate. Not having either of these things, and thinking that I should at least try to be somewhat traditional, I went to one of the local Chinese stores and bought both. I have other bottled inks, of course, but I'm told that they're inferior for this kind of work.

The ink-production technique goes more or less as follows: put a few drops of water on the inkstone, grind ink into it, dip your brush into it, remove excess by blotting on a cotton towel, dip your brush again, and so forth until you have a colour of ink you like. For a good video tutorial on this part of the process, click here.

Of course, this looked too involved and fussy for me, so I abbreviated the process to this: a few drops of water on the inkstone, grind ink, dip brush, see if it's the right concentration, paint.

For my brush, I decided I'd at least try to use my one bamboo brush. It's a reasonably good-quality brush, I think; I'm just not very good at making these kind of brushes do what I want. Apparently the brushes used for ink-wash painting are similar to the brushes used for calligraphy (I think they should be the same, so that I don't have guess which one I have). They traditionally consist of a bamboo handle with goat, horse, cattle, sheep, rabbit, marten, badger, deer, boar and/or wolf hair. The brush hairs taper to a fine point, which is apparently crucial to this style of painting. I think mine might be goat hair, but the label is in Japanese, so I'm not sure.

A final warning from the Wikipedia page:

Once a stroke is painted, it cannot be changed or erased. This makes ink and wash painting a technically demanding art-form requiring great skill, concentration, and years of training.Well, I won't be bringing years of training—or any training, really—to today's activity, so it could get ugly. Before it gets ugly, however, here is a nice little video of a master artist drawing a sparrow using this technique.

For today's elephant, I thought about buying rice paper, then decided I was too inexpert to splash out on relatively expensive paper. So I used sketchpad paper.

For my ink, I bought a small inkstick at a local Chinese store for three dollars, and an inkstone for another five dollars.

For my brush, I had this brush, which I suddenly realized I'd never used before. Now I'm wondering what happened to the much-maligned first bamboo brush I had. Perhaps I disliked it so much that I threw it out. Now that would be a first.

I quite liked grinding the ink—in fact, it's probably what I liked best about this activity. I dropped water on the inkstone by squeezing it out of my brush, and ground enough ink to make a reasonably saturated black.

After this, I more or less just played with the brushstrokes, using the side, the point, both the side and point, and so forth. I don't think I ever really got the hang of ink-wash painting, but it wasn't for want of trying, as you'll see in my series of drawings below, in the order in which I drew them.

A few tips if you decide to try this:

1. The wetter the brush, the more ink it will hold. This seemed counter-intuitive to me, but when my brush was wet (but not soaking), I got the best blacks.

2. Swirling the brush in the ink, or in a paper towel, makes the finest points.

3. A dry brush creates streaky patterns, so if you don't want that effect, keep the brush relatively wet.

4. The ink is definitely ink-o-philic, meaning that it's deeply attracted to itself. If you try to layer new ink on something that's still damp, it will spread, while also absorbing the new ink and reducing the impact of the lovely rich black you thought you'd get. Even if you put new ink over dry ink, it's still going to absorb to a certain extent. I was never quite able to achieve a deep, rich black. Then again, maybe I should blame it on the porous paper.

5. Playing with the brushstroke is quite fun. I went from flat and wide to fine and back again within the length of a single short line.

When I bought the inkstick and inkstone, the man in the store tried to steer me towards the liquid ink. Perhaps I should have listened to him, because I was a bit disappointed in the blacks I was able to achieve. I did, however, really like using the brush, and now wonder what it was that I didn't like about the one that's gone missing.

I'm not sure I'd rush to try this again, mostly because I didn't feel I had the knack for it. I never really figured out how to create subtle shades of grey and, no matter how many times I tried, I couldn't figure out how to make a single brushstroke go from black to grey. Maybe if I'd thought of it more as a painting technique and less as an ink technique, I'd have had more affinity for this process.

I did like making the ink, however, so I may try this again. But perhaps without trying to imitate sumi-e masters next time.

Elephant Lore of the Day

From the sublime art of Eastern ink-wash painting, we come to the ridiculous art of concrete roadside-attraction elephants.

In 1927, I.L. Perry opened Perry's Nut House in Belfast, Maine. Perhaps playing a bit on the name "nut house", Perry's included far more than peanuts and pecans.

Located on the coastal road to Bar Harbor, Perry's featured giant animal sculptures outside, as well as an indoor display of exotic nuts, and an "Animarium" featuring stuffed exotic animals. Among the star attractions at Perry's, however, was a life-sized concrete elephant, followed in later years by a pair of wooden elephants named Hawthorne and Baby Hawthorne.

Originally a sea captain's home, Perry's Nut House was actually Perry's Cigar Factory before the eponymous owner decided that he needed a larger shop for his nut business. Taking advantage of a bumper crop of pecans in Georgia, Perry sold "a taste of the South" to people in Maine, later adding a display of curios collected on his travels.

In time, Perry's reputation grew, not only for the nuts, sweets and jams he sold, but also the quality novelty goods he carried, including seahorse water pistols and fine cigars. In its early heyday, Perry's Nut House was popular with well-known artists, actors, musicians, and even political figures such as Dwight Eisenhower and Eleanor Roosevelt.

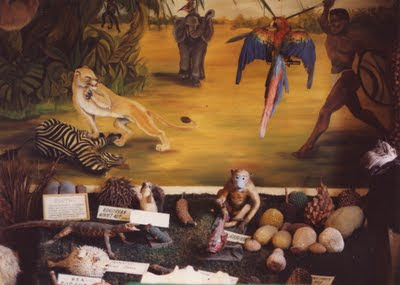

The Nut House was also renowned for its weird displays. The large shop contained stuffed bear cubs wearing boxing gloves, stuffed alligators, a water buffalo shot by Teddy Roosevelt, and even a stuffed gorilla.

Although Perry retired and sold the business in 1940, later owners continued to add oddities such as funhouse mirrors, a huge albatross, "a man-eating clam" and "Jay the Forgotten Mummy". Jay was supposedly removed from Egypt by a wealthy family, so that they could throw fashionable mummy parties. When Jay became an unwanted family possession, he was offered to Perry's Nut House, which readily accepted.

Among Perry's most popular and iconic attractions, however, were the succession of elephants that greeted visitors. Generations of tourists posed first with the unnamed concrete elephant, and later with both Hawthorne and Baby Hawthorne. In time, as the elephants deteriorated, they were refurbished, and eventually replaced.

|

| Hawthorne was added first. Baby Hawthorne joined the herd in 1961. Source: http://www.cardcow.com/323493/perrys-nut-house-famous- elephants-belfast-maine/ |

Over the years, the displays declined. Many were damaged and never properly repaired, or simply disappeared. In 1997, the shop's owners auctioned off the various curios and other historical memorabilia, including letters from both Dwight D. Eisenhower and Eleanor Roosevelt, extolling the virtues of Perry's Nut House and its wares. Hawthorne was sold to the Colonial Theater in Belfast, where he sits on the building's roof. Baby Hawthorne was also purchased by the Colonial Theater, and ended up in its lobby.

Although the plan in 1997 was to turn Perry's into a condominium development, tourists continued to come searching for the iconic nut house and its displays, and the business was reborn. The current owners have re-acquired and restored many of the displays. Hawthorne II and Baby Hawthorne II, however, remain at the Colonial Theater, and the new owners of the now-thriving nut and fudge shop have begun collecting donations towards acquiring a new elephant for Perry's.

|

| Hawthorne II on the roof of the Colonial Theater in Belfast, Maine. Photo: David Lyon Source: http://www.boston.com/travel/blog/2010/03/free_range_musi.html |

To Support Elephant Welfare

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information

on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

Elephants Without Borders

Save the Elephants

International Elephant Foundation Elephant's World (Thailand)

David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Elephant Nature Park (Thailand)

That's a gorgeous—and very fun—image they chose. Your children have excellent taste!

ReplyDelete