I've seen animals made with wire and needle-felted wool, and I've made needle-felted animals without wire. Spun cotton on wire was a new activity for me, however, so I thought I'd try it for today's elephant.

The technique of wrapping spun cotton over wire was originally used to make Christmas ornaments. Usually made in the form of little dolls, the figures often had paper or bisque faces.

|

| "John Bull" spun cotton ornament, 1890s. Source: http://myvintagechristmasdecorations.com/1890s-early-antique-vintage- german-spun-cotton-christmas-ornament-john-bull/ |

The heyday of this type of ornament appears to have been the late Victorian period, from the 1880s to the first decade of the early twentieth century. In recent years, however, there has been a revival of interest in spun cotton figures. Many artists working with this technique still use paper and bisque faces in their work, as well as vintage trims. Others—including my personal favourite, artist Maria Pahls—produce figures made entirely of wire, spun cotton and paint.

|

| Spun cotton ornament by Maria Pahls. Source: http://www.etsy.com/listing/76299740/reserved- listing-sold-spun-cotton |

Vintage spun cotton figures have also become highly collectible. Wear and tear can take a significant toll on this type of ornament, but a Victorian ornament in good condition can sell for well over $100. New ornaments and dolls created by artists sometimes sell for substantially more.

|

| Spun cotton ornament from Old World Primitives. Source: http://www.etsy.com/listing/85500990/cat-ornament-spun-cotton-christmas |

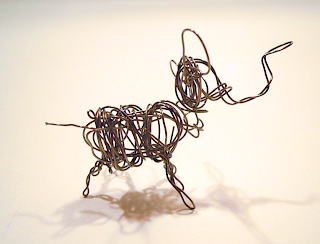

For today's elephant, I decided to make the kind of figure that involves wire, cotton and paint. I also wanted to make something quite small.

Since I didn't have a clue what I was doing, I looked up instructions online. I was mostly interested in learning how the cotton attaches to the wire armature. There are several sets of instructions if you do an online search for "spun cotton ornament", but I found this set helpful as a place to start.

I used the same wire I'd used for my three-dimensional wirework elephant several months ago. It's a 26-gauge wire made of steel, and is reasonably pliable. I didn't want anything too stiff or too heavy for small figure like this, and I didn't care if it was rigid, so this size was fine.

The armature I made was relatively simple, as it was mostly just a form on which to wrap the cotton. Some people suggest wrapping the armature with masking tape, but I didn't like that idea, so I decided I would just wrap the wire with as much cotton as it took.

The cotton I used is not traditional cotton roving—which I couldn't find anywhere today—but a roll of cotton batting that I picked up for $1.50 at a discount store.

To start wrapping the cotton over the armature, I cut narrow strips of cotton batting, which I then thinned out a bit.

Next, I spread glue over the wire, and began wrapping cotton over the armature in an admittedly eccentric way. I quickly discovered that strips of cotton batting are pointless for something this small. I ended up using patches rather than strips, building up the figure with blobs of cotton rather than neatly wrapped lines.

According to most instructions, once a basic layer of cotton is on the armature, the next layers of cotton you use will adhere to one another. Mine didn't, so I touched glue to the underlayers, then stuck more cotton on top.

I shaped all of the areas with my fingernail, as my fingers tended to get sticky quite quickly, pulling the cotton away. It's not a bad idea to keep a moist cloth nearby to clean your fingers from time to time. In fact, it occurred to me after I was finished that it might have been a good idea to handle the whole thing with a piece of plastic wrap to avoid sticking to it.

Once I was happy with the elephant, I set it aside to dry. I had also decided to add a little beret and bowtie to the elephant to make it a little less plain when I was finished.

I didn't have time to leave the glued cotton to dry overnight as they suggest, so I took a hairdryer to this little guy. It took about ten minutes of blasting with the hairdryer to get it dry enough to paint.

I started by painting the elephant itself with grey acrylic paint. Painting this was, er, interesting. The paint, no matter how thick, sucked right in to the cotton batting, making multiple layers of paint necessary. The wetness of the paint also affected the cotton surface. The wetter the paint, the more the cotton absorbed, fluffing up and detaching from the figure. It was a bit of a balancing act to get the paint to adhere thickly enough, without destroying the surface.

Paint also makes the surface very wet. It's hard to find a way to hold the figure without making the paint squish out onto your fingers like a sponge. I ended up mottling the surface a bit as paint squeezed from one area to another, which meant a bit of repainting. It wasn't completely frustrating, but it was a bit tricky.

I let the grey paint air-dry for about fifteen minutes, which was enough for me to be able to pick it up without getting paint on my hands. Then I blasted it with the hairdryer for about five or ten minutes to set the paint so that I could add the rest of the colours.

It took less time to paint everything else than it had taken to paint the grey, and I still kept noticing gaps in the grey paint. It was easy enough to touch these up, but it surprised me to see them.

This wasn't a terribly time-consuming activity and, outside of the slight aggravation of cotton sticking to my fingers, it was rather fun. Making an armature is easy, and wrapping it with cotton needn't be an exact science, so the final result is likely to be an eccentric surprise. For me, that's part of the appeal of this activity.

I don't think I'm going to go into business making these anytime soon. I'm glad I tried it, however, because little objects like this would make fun gifts for friends.

Elephant Lore of the Day

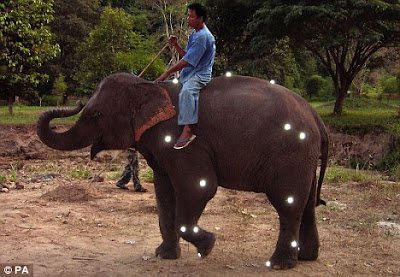

In 2010, scientists discovered that elephants have "four-wheel drive". Unlike other quadrupeds, which have "rear-wheel drive"—accelerating with their hind legs, and braking with their forelegs—elephants apply power and braking independently on each leg.

Studies by the Royal Veterinary College in London, England further discovered synchronize their legs vertically rather than horizontally. This means that each limb functions as a separate sort of spring, providing propulsion, braking and lift.

|

| Reflective markers were placed on the elephants for motion-capture. Photo: ©PA 2010 Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1262262/Elephants-legs-propel- just-like-4x4.html |

To determine how elephants move, researchers analysed six young Asian elephants in Thailand using 3-D motion-capture technology. The elephants were fitted with reflective markers at strategic points along their bodies. They were then guided along a force-sensitive platform through all gaits, filmed by seven infrared cameras. Changes in position were then fed into a computer for analysis.

Interestingly, the studies also showed that elephants have a lot of "bounce" in their limbs, especially when moving at faster speeds. This, ironically, gives elephants about the same muscular efficiency as humans, which is why elephants tend to avoid running.

|

| African elephant at the Oakland Zoo, Oakland, California, 2012. Source: http://www.oaklandzoo.org/blog/2012/04/05/stepping-through-zam-day-7- savannah-module/elephantwalkbysteve/ |

To

Support Elephant Welfare

Elephant

sanctuaries

(this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information

on a number of

sanctuaries

around

the

world)

No comments:

Post a Comment