Today I thought I'd try something that I haven't done since I was a kid: toothbrush painting.

People have looked after their teeth in a variety of ways since prehistorical times. Chew sticks, twigs, feathers, bones and porcupine quills have all been found in various archaeological digs. The first known toothbrush dates from 3000 B.C., in the form of a twig with a frayed end.

For millennia in India, the twigs of the neem or banyan tree have been used. The end of the twig is chewed until soft and frayed, then is used to brush the teeth. In the Middle East, twigs from the arak tree are used in a similar fashion. Both neem and arak twigs have antiseptic properties.

Pastes made with baking soda, chalk and other similar abrasives have also been used throughout history, simply rubbed across the teeth with a finger. In 1223 A.D., a Japanese Zen master reported that he had seen monks in China cleaning their teeth with brushes made of horsehair, attached to a handle made of ox bone.

Since 1498 A.D., the Chinese have used a form of bristle toothbrush. It is believed that use of this early toothbrush spread to Europe along trade routes, and is the prototype for the toothbrushes we use today.

Toothbrushes were not mass-produced until 1780, when they were marketed by Englishman William Addis. In 1770, Addis had been jailed for causing a riot. During his imprisonment, he decided that he could improve on the usual method for cleaning teeth: rubbing a damp rag with soot and salt across the teeth and gums. He took a small animal bone, drilled holes in it, got some bristles from a guard, tied the bristles into tufts, and glued the tufts into the holes. Addis became very rich from his invention, and the company continues to this day under the Wisdom Toothbrushes brand.

By 1840, toothbrushes were being mass-produced across Europe and in Japan, with pig bristle used for cheap toothbrushes and badger hair for a higher-quality version. The first toothbrush patent was applied for in the United States in 1857, although mass-production in the U.S. didn't begin until 1885. The first U.S. brushes had bone handles, with Siberian boar hair bristles. Unfortunately, animal bristles have never been an ideal material, since they don't dry well, and retain bacteria.

In 1938, the chemical company DuPont created nylon fibres for use in toothbrushes, and the first synthetic-bristle toothbrush went on sale in February of that year. Interestingly, cleaning teeth was not routine until the

Second World War, when soldiers were required to brush their teeth every

day.

I couldn't find any information on the genesis of toothbrush art, but it probably goes hand in hand with the invention of synthetic brushes. Today, toothbrushes are used in art primarily for spatter painting, although some artists also use them as actual brushes.

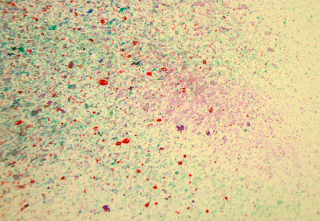

For today's elephant, I decided to try the spatter method. I unearthed a new kiddie-sized toothbrush that my sister had given me as a joke a few years ago, which seemed like the perfect size.

For paints, I opted to use a set of cake watercolours that I've had for at least 20 years. I like the pan size on these, which seemed perfect for the toothbrush I had.

I started with a slightly watery paint consistency. It's not completely liquid, but it's also not all that thick, either.

To spatter paint with a toothbrush, you simply use your thumb—I actually found that my index finger often gave me more control and directionality—running it against the bristles to flick paint onto the paper.

It's exceedingly hard to control, just like my paint-flicking spatter-painting experiment, so it's a good idea to use something as a sort of mask. I didn't want hard lines like you'd get with an actual masking fluid or tape, so I simply folded a bit of aluminum foil and held it near the paper while I flicked. It wasn't foolproof by any means, but it helped me concentrate some of the paint, some of the time, to a certain extent.

Once I could see the basic design taking shape, I got a bit more confident.

The droplets are quite fine, and depend primarily on the thickness of the paint loaded onto the toothbrush. If I used a slightly wet toothbrush and ran it over the cake of paint to make a fairly thick pigment, the droplets were heavier, more opaque, and less splattery. Obviously, at the opposite, more watery, end of the spectrum, the paint is fainter, finer and spreads over a wider area.

Your flicking technique also comes into play. The more gently you run your finger or thumb over the brush, the lighter the spray, and the more limited the area. The more violent you are, the more the paint flies.

After I'd layered and thickened most of the design, I added a bit of black to shape things a bit. My ability to do this was limited within the time I had today, but you get the idea.

I also added a bit of white to try and create some highlights—which didn't really work—and a tusk—which sort of worked.

I kind of like the dreamy quality of the final result, although I wish I'd had more time to shape things. I didn't really love this poor man's airbrush technique, however, because of the lack of control, but I might try it again with proper masking and a lot more time to play with it.

Elephant Lore of the Day

Elephants need dental checkups just like humans. At most zoos, elephants are trained to open wide for the dentist, who checks to see that there are no tooth fragments that need to be pulled.

Dental care also applies to an elephant's tusks, since these are simply very long teeth. In late 2010 in Kerala, India, a 27-year-old elephant named Devidasan developed a painful 48-centimetre (19-inch) crack in one of his tusks. Dr. C.V. Pradeep, a local dentist, decided to try filling the crack with the same resin used to repair human teeth.

The operation lasted two hours, took 47 tubes of resin, and required specially modified equipment. One of the challenges was that there were no mobile x-ray machines big enough. The elephant was tranquilized, however, and was cooperative throughout the procedure.

The repair not only got rid of the elephant's toothache, but also removed the possibility of a potentially deadly infection, should dirt have gotten into the crack and remained there.

To Support Elephant Welfare

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

This was such a beautiful post. I didn't realize you could do such great artwork with a toothbrush. Thanks for the share. Have a wonderful day.

ReplyDeleteDentist Philadelphia

Awww...thank you so much! It's messy but so fun! Have a wonderful day, too.

ReplyDeleteElectric toothbrush china

ReplyDeleteGreat share! Thank you so much for sharing all this wonderful info with the how-to's!!!! It is so appreciated!!!

ReplyDeleteDentist in Bangalore